Spotted Wing Drosophila Monitoring Report June 24, 2016

go.ncsu.edu/readext?416941

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲The research sites where we are collecting data are rich environments with many different species of insects. Pest species, including spotted wing drosophila (SWD), have found these sites to be suitable environments, but they are not the only flies, nor the only Drosophila to take advantage of the conditions. Other species of Drosophila (also called vinegar flies) inhabit these areas and may interact with SWD populations.

Other native, non pest Drosophila species may out compete SWD in rotting fruit, preventing SWD from being able to take advantage of these extra resources. Native drosophilids also aid in the decomposition of fallen fruit in the field, reducing the amount of material that may draw in SWD from outside environments. Females of native Drosophila species have much small egg laying devises (ovipositors) than female SWD, and this difference is used in identifying flies in traps. In fact, it has been hypothesized that female SWD evolved the large, heavily serrated ovipositor that allows to infest undamaged fruit in response to competition from other Drosophila species in rotting fruit. See this recent paper for more information on that theory.

A wide variety of Drosophila species are drawn to traps at the research sites. There are many different species of drosophila, and it is important to recognize that not all these flies are pests! The image below includes both non-SWD and SWD flies.

In this picture, SWD are marked with a check; non-SWD drosophilids are marked with an X. Photo: Grant Palmer

In addition to other Drosophila species, beneficial predatory insects such as dragonflies are also present at our sites. Research is also being done on parasitoids that may be able attack SWD. These parasitoids could be critical in managing SWD populations.

Many growers have drainage ponds that make great habitats for beneficial predatory insects like dragonflies. This one here was perched on one of our trap posts. Photo: Grant Palmer

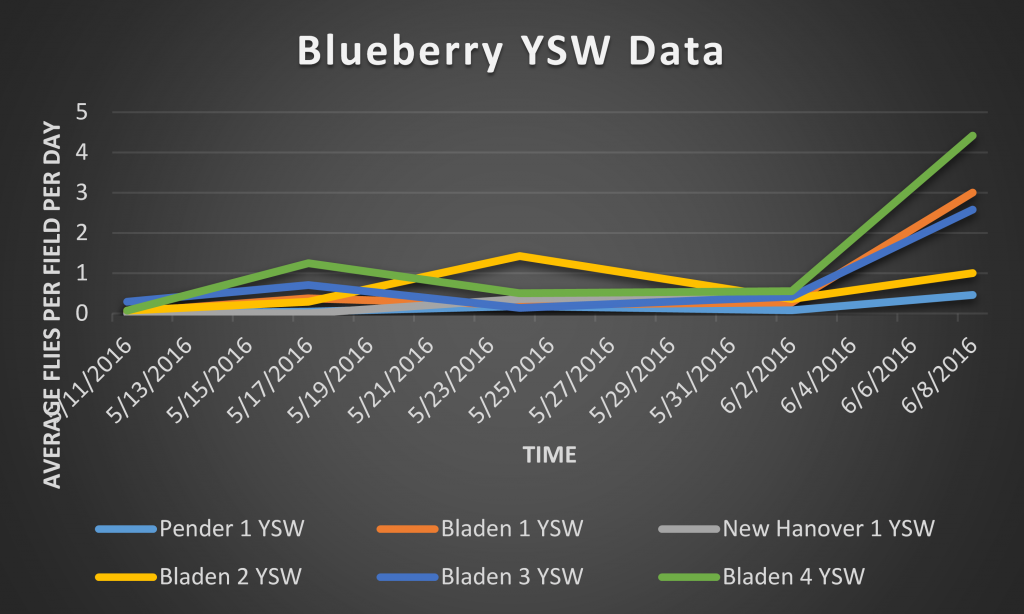

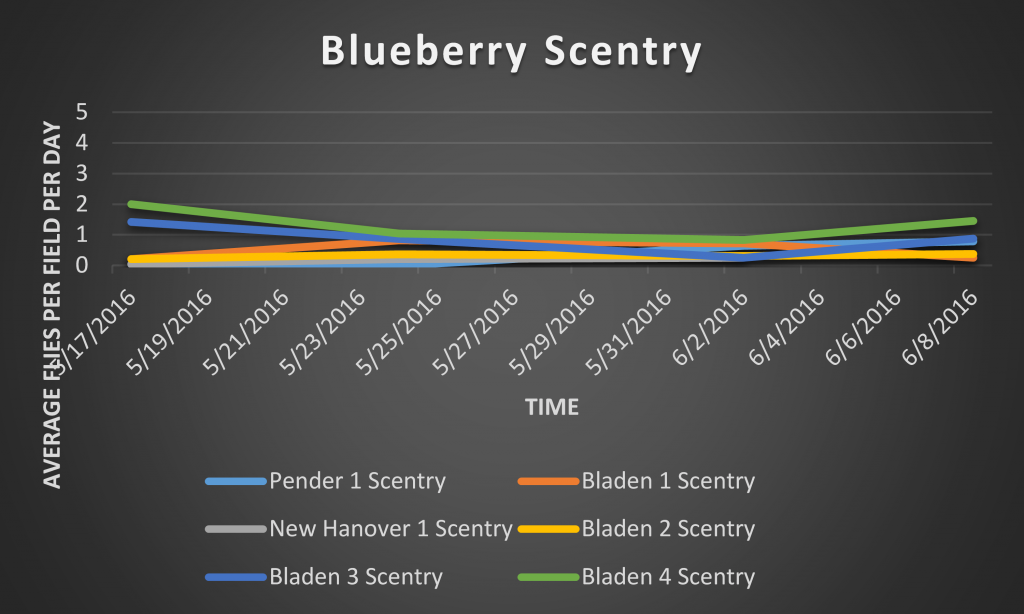

The average number of total (male and female) SWD captured per site per day are presented in the figures below. Trapping began at six blueberry fields on May 11, 2016. Scentry lures were not available until May 17th, so these were deployed at blueberry locations during the second week of monitoring.

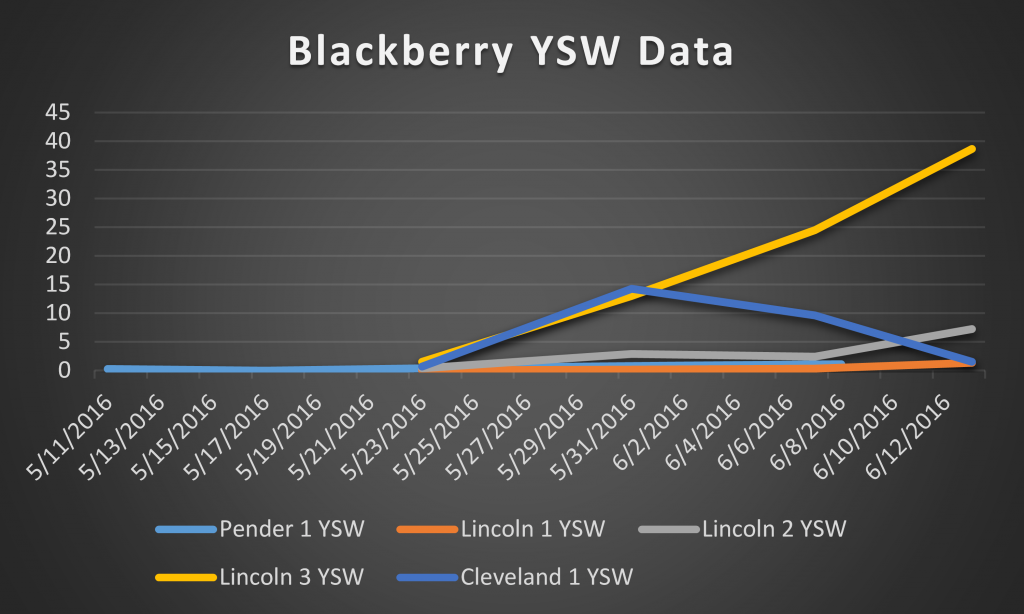

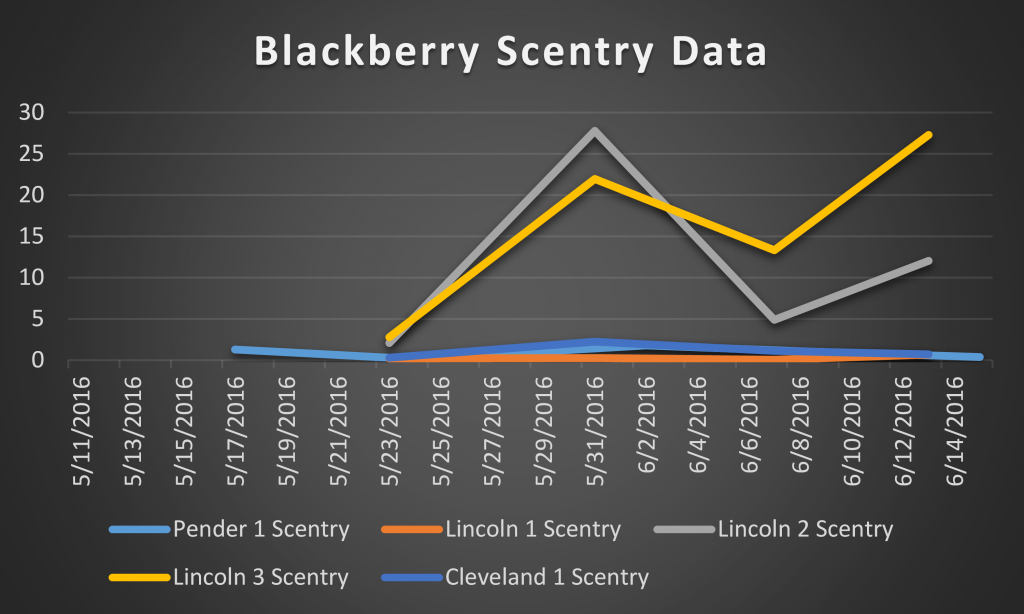

We are monitoring a total of five blackberry fields, and first checked traps on May 17, 2016. SWD trap captures are generally higher in blackberry fields as compared to blueberry fields.

Data is continually processed and will be updated weekly as it becomes available.

Female SWD collected in traps may have fewer mature eggs than those collected directly from fruit. Graduate student Katie Swoboda-Bhattarai in our laboratory is studying this observation further, and we are particularly interests in these results as they could potentially explain the striking peaks and valleys in the blackberry Scentry trap data.

More information